Shape and Substance No. 2: Beyond Moralizing

Shape and Substance

Paul Hooker

15 November 2024

No. 2

I want to follow up my comments on moralizing preaching with some additional thoughts. Several of you have been kind enough to respond with some critique, for which I am immensely grateful. Your comments have been thoughtful and wise. I might summarize those reactions as concern that, in this era of diminished moral responsibility at both the top levels of government and across society in general, we cannot afford to lose the moral imperative of preaching. Additionally, a few of you have expressed concern that you would prefer moral directives over flights of preacherly fancy.

It seems important to me to distinguish between moralizing and moral vision. The former amounts to someone telling me what to think or do, most often accompanied by all manner of homiletical hand wringing over the state of the world. The latter, it seems to me, sets forth a compelling image of beauty, hope, and peace, and invites us to enter that vision and absorb its values and attributes.

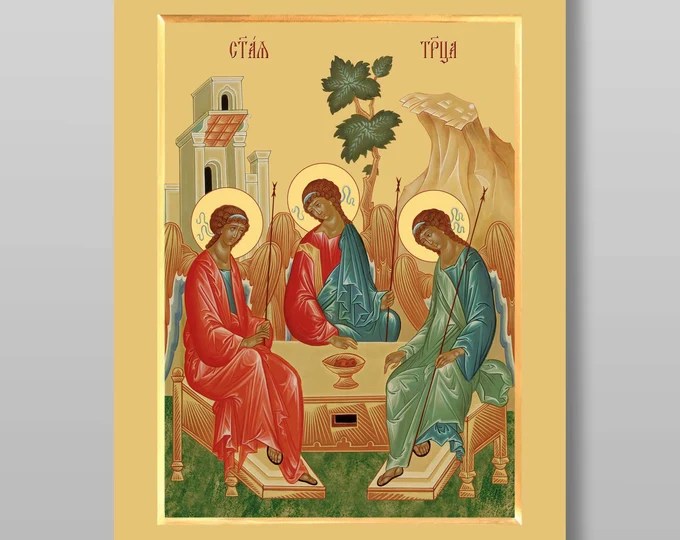

Above is the famous Russian icon, painted by Anton Rublev in the early 15th century. There is a tradition in Russian iconography of depicting the visit of the three angels to Abraham beside the oaks of Mamre (Genesis 18) to convey to him the news that he would have a son to inherit the blessing. In both Eastern and Western Christianity, the visitation of the angels is taken to be an image of the Trinity. So much so, in fact, that in many renditions the background of the dwelling and the oaks still visible in Rublev’s icon disappear completely in favor of the three figures, each of whom bears specific attributes associated with one or another person of the Trinity.

A Google search of “Rublev icon” will open for you the world of commentary about the icon and its theological significance, far more than I have time or space to explore here. I only want to illumine one aspect of the painting. You will note that the three figures (the Father in the center, the Son at the Father’s right, and the Spirit to the Father’s left) are seated at something like a table, on which rests a vessel of some sort. Perhaps the vessel holds the water, bread, cakes, or meat Abraham has called to be prepared (18:2-8). Or, as some have suggested, perhaps is a chalice that holds Eucharistic wine, and the three are gathered at the Eucharistic table. Part of the beauty of art is its flexibility and openness to wonder.

I rather like the Eucharistic reading of the icon, and I note one thing further. As on looks at the painting of the seated Three, there appears in the center foreground an open space, as though there is a place at the table presently unoccupied and waiting for the arrival of the final guest. As one approached the painting, one has the sense that this place belongs to the viewer, that the Three invite each and all of us to enter the fellowship of Beauty in and through the Sacrament.

I want to suggest that, like the Eucharist, the best preaching is an invitation into the divine fellowship. I want to suggest that, beyond all the shoulds and oughts we are tempted to adjure, the most effective means of transforming life and lives is the offer of a place more lovely, more compelling, more fulfilling than any moralizing can finally be. I want to suggest that preaching point in the direction of Beauty and remind us that there is a place waiting for us at the table.

I am not advocating sacramental escapism, dousing the very real fires of a passion for justice with sacramental wine. I am not suggesting that the Beautiful Vision does not carry with it some expectation of change on the part of those who see it. Precisely the opposite. As Reformed theology has taught for generations, to be the invitee into the divine relationship is to become what one was created to be, not merely continue being what one already is. However, we change not in hopes of getting an invitation to the feast, but because we already have that invitation in hand and want to dress appropriately. Beauty makes us want to become.

The coming years will have more than their share of moral horrors on which to reflect (although, one hopes there may be some good in them, too). We who wear the homiletical mantle will be tempted weekly to decry the ugliness we see displayed on the evening news. Some of that, I would agree, is necessary. But can preaching be more than decrying the ugly? Can there be also and finally a vision of Beauty that draws us beyond the grit, grime, and grimace of the daily grind? Can there be an opportunity not to escape but a summons to fulfillment? Can there be a sanctified imagination that asks what is possible, not merely what is practical or pragmatic or politic?

I hope so. What about you?