God, Breathing—some thoughts about creating a future

Let’s start at the beginning. “In the beginning,”—bereshith, in Hebrew—begins the story in Genesis 1:1. It has always fascinated me how spare and direct these first sentences of the Bible are. “In the beginning”—the narrator says, as if he or she is privy to things before there were things to be privy to. As if she or he is party to knowledge inaccessible to mere mortals, but the rest of us must accept his words as a sort of curtain drawn across the stage of human consciousness behind which we are not permitted to peek. As if it were possible to know that which is cloaked in eternal darkness, even if that darkness already contains all the light that will ever be. In the beginning—bereshith …

Bara’ ‘elohim—“…God created….” As far as I know, the Hebrew Bible, which uses this verb bara’ on a number of occasions, never uses it to describe human agency, but only the act of the Creator, either directly or indirectly. I take this to mean that to create is to invade a province that belongs to the Creator. To use it of ourselves—or to encourage our children to “be creative,” or (heaven forbid!) to preach sermons on the subject of creativity—is, it seems to me, Promethean in the extreme. We are stealing the fire of the gods here.

But, as they say, fools rush in… For the next few minutes, I invite you to think with me about creation and creating. I’m going to suggest that, when we exercise our creativity—and especially when we exercise it in the service of faith—we are doing something only God can do. We are mimicking the Creator. There is something a little dangerous about that. There is also something a little divine.

Look again at Genesis 1. If you’ve studied ancient history, you know that ancient Babylonian culture told the story of its origins in a mythic account tthat has come down to us as the enuma elish. It was the story of a great cosmological struggle between the patron deity of Babylon, Marduk, who was a warrior god, against the terrifying power of Tiamat, the chaos dragon. The battle is joined, and Marduk isn’t faring too well. Marduk has loosed all but one of his arrows at Tiamat, only to have them bounce harmlessly off her scaly hide. At last, nearly disarmed and powerless before her towering might, Marduk prepares to die. Tiamat opens her mouth and prepares to swallow Marduk. But at the last moment, Marduk fires his last arrow into her gaping maw; it penetrates her stomach and sends her into her death agony. Marduk speeds the process along by leaping atop her still-writhing form and carving her up with his sword. Of the pieces of her carcass Marduk creates the world, and with her black blood he makes human beings, forever to be his servants in gratitude for his victory. So the Babylonians believed.

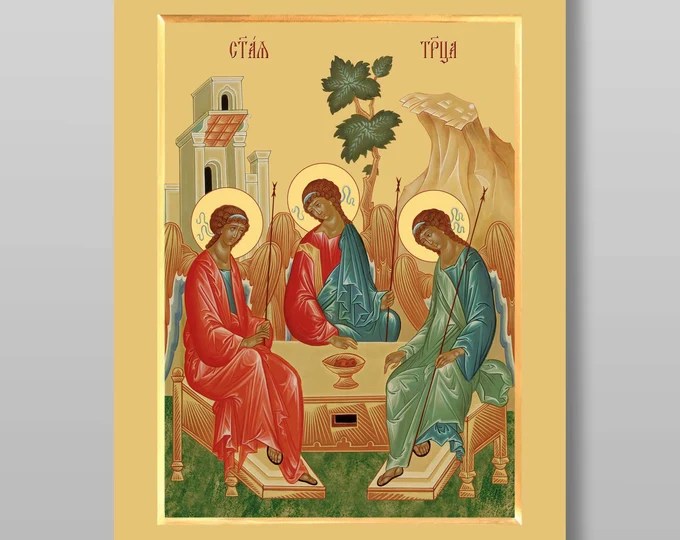

Scholars have thought for generations that Genesis 1, the first of the biblical stories of creation, was written while the Israelites were in exile in Babylon. They heard the enuma elish recited every year at the Babylonian New Year festival, and they decided to write their own version. But, as exiles and prisoners often do, they made their story something of a parody of the stories of their captors. Tiamat, the chaos dragon, becomes tehom, the Hebrew word for “the deep,” an infinite, formless, shifting, but not particularly ravenous body of water. And instead of God locked in some life-or-death fight with a dragon that overmatched divine power, God simply “breathes”—the Hebrew word ruach, translated “Spirit” here can also mean, “breath”—across the watery surface. And perhaps in the way breath across water creates ripples, the divine breath began to ripple the landscape of reality. And then, when the moment is right, God speaks…

The Hebrew word is vayyehi, “let there be.” It’s an interesting word, this first divine utterance. Grammatically speaking, it’s not an imperative—“do this, go there”—but a jussive—“let there be.” It’s an invitation for something to happen, a space within which something that isn’t, might come something that is. Stephanie Paulsell and Vanessa Zoltan observe about this word:

God does not decree creation like an authoritarian ruler signing executive orders. God sets unpredictable, creative possibility loose in the world: let there be light, let there be fish in the sea, let us make human beings in our own image.[1]

Something about creativity—divine creativity and, I think, human—is not prescriptive but permissive. It does not so much force as to allow; it does not so much control as to conduct. Creativity sets loose the unpredictable, the unexpected, the unprecedented into the world, and waits for it to turn the world upside down.

But perhaps we are getting ahead of ourselves, or at least ahead of the story. I mentioned at the outset of these remarks that the first word of Genesis 1—bereshith, “in the beginning”—is like a curtain drawn across the stage of human consciousness behind which we are not permitted to peek. But where knowledge fails us, imagination may succeed. So let me invite you into an act of imagination.

Jewish mystics from the 17th century onward have toyed with a concept called tsimtsum. The word means “contraction” or “withdrawal,” and since the 17th c. it has been used as metaphorical figure for what happens before the bereshith. In truth, it was the answer to a problem: Jewish thought postulates that God is limitless, all-inclusive, Infinite, and without internal division or dichotomy. There is even a special name for this limitless one: ‘Ein Sof, which means, literally, “without limits” but is often translated, the Infinite or the One. In the silence before the beginning, say the mystics, there is and can only be the Infinite. But if that is true, then how can anything that is not the Infinite—including the whole of creation and all of us—exist? There is no place and no condition that is not the Infinite, so there is no room for creation. In response to this problem, the mystics suggested that before uttering the first vayyehi, “let there be,” the Infinite underwent tsimtsum. That is, the Infinite—“God” if you will—withdrew within God’s self, contracted, and thereby made a space within God that was not God, and into that space could come into being all that eventually comes to be: the sun, the stars, the skies, the seas, the land, the living beings, and yes, even the likes of us. Tsimtsum is the moment of infinite possibility, in which all things exist in potential and nothing exists in particular. In my imagination, tsimtsum is God inhaling, drawing into the divine self the breath of the divine self, before exhaling the first word: vayyehi—let there be. In my imagination, the first act of creation is not God speaking. The first act of creation is tsimtsum, God, breathing.

Some of you are asking, now wait a minute; Genesis doesn’t say anything about this. Some others of you are remembering right about now St. Augustine’s facetious answer to those who ask, What was God doing before creation: “Preparing hell for those who pry into mysteries.”[2] Others of you, perhaps being better versed in paleogeology, are thinking, come on now, we know it didn’t happen this way. There are dinosaurs and trilobites and protozoic amoebae. And you’re right, all of you.

What I am suggesting is that you exercise your imaginations, allow the poet inside you to slip the leash and wander free for a moment. If you can do that, even for a moment, if you can grant me what Samuel Taylor Coleridge once called “the willing suspension of disbelief,” you can see that at the beginning of every creative act there is an emptiness, a silence, an open space. And in that emptiness, all things are possible, and there is no limit to creative possibility.

Every poet knows that, before beginning to write every poem, there is a blank page (or, in my case, screen) on which nothing is written. That blank screen holds the infinite possibility of every word known to humankind, and even words not yet known or thought of. When the first word is written, that infinite possibility begins to take form and structure, becomes a word, then a line, then a stanza, and finally a poem. But before every poem, there is an emptiness.

Every musician knows that, before the first note of a piece is played, there is a silence, a quiet. That silence holds the infinite possibility of every note and every sound including those not yet known or played. When the conductor’s downbeat falls and the first note is played, that infinite possibility begins to take form and structure, becomes a phrase, then a melody, then a passage, and finally a symphony. But before every musical piece, there is an emptiness.

Now why have I put you through all this? I promised you in the beginning that I wanted to observe something about creativity. I want to suggest that to create—and by creating I don’t just mean writing a poem or playing a piece of music, but also making plans for the future of a life, a community, a nation, and a world—to create is to mimic God.

We have this notion that creating our future is about making choices and sacrifices, about commitments of time and energy and resources, and perhaps most of all, to apply energy and effort to ensure that our will is done, our vision is brought to fruition, our project is successful. We think that creating is about imposing our will on chaos by act of main force. That may all be true, or most of it, anyway.

But it is not where creativity starts.

If it is true that to create is to mimic God, then perhaps creating begins not in pressing forward with an agenda, but in withdrawing in silence and patience, allowing the emptiness to fill with infinite possibilities, some of which we have not imagined. Possibilities that might elude the snares of partisan politics, the labels of progressive or conservative. Possibilities that might reveal a future no one has imagined yet because our vision is captured by a past no longer sustainable. Possibilities that might have us become something we have not yet imagined we are.

And if we can wait, can practice a season of silence (instead of shouting down the opposition), perhaps when the vision begins to form, it will be possible not to force it into birth, but simply to release it, to let there be… let there be light, let there be land, let there be life, let there be community, let there be hope. Creativity is not about force; it is about permission. It is not about requiring; it is about allowing.

I don’t know what will be the shape and substance of our future as a nation among the peoples of the world. But I am increasingly convinced that, if we are to create a sustainable future, to say nothing of creation as a whole, it will not merely be the result of one agenda stamping out another. It will be something none of us has imagined yet. It will come into being not because we force it but because we release it. We will create a future when we stop shouting about what we know, become comfortable with silence and emptiness, and listen to the sound of God, breathing.

[1] S. Paulsell and V. Zoltan, “Creativity: The Joy of Imagining the Possible, Imagination, and Joy,” in Joy: A Guide to Youth Ministry, Sarah Farmer and David F. White, eds. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020 p. 214.

[2] Augustine, Confessions, 11.12.